Edward Niedermeyer stood at the curb of a neighborhood park in Chandler, Arizona, and watched as a driverless Chrysler Pacifica minivan rolled to a stop.

The former journalist and auto-industry critic, who is now the communications director for the Partners for Automated Vehicle Education, was on assignment for TechCrunch. He was about to take a ride in a driverless vehicle for the first time in his life, on a quiet mid-morning with few pedestrians or cyclists out and about.

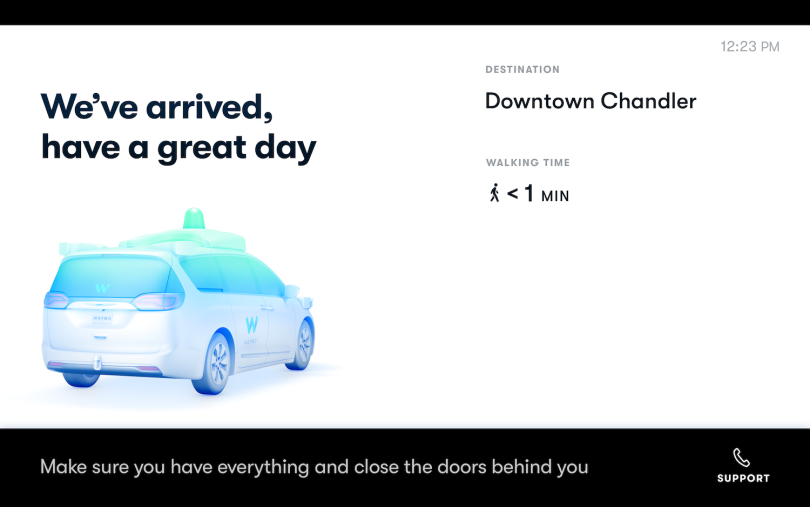

Niedermeyer summoned the car through a mobile app, and unlocked its door with a Bluetooth signal. After being greeted by the voice of a live rider support agent and watching a safety video, he buckled in and pushed the “Start Ride” button. The steering wheel began to turn by itself.

As the car veered into the public roadway, an animated 3D depiction of the surrounding streetscape, with cars, stoplights and pedestrians — a simulation of what the car “sees” — played on a screen mounted to the seat in front of him. He turned on some hip hop over Google Play and learned back. He was on his way.

For a man who has made a career of thinking and writing about cars, some of this was old hat. Niedermeyer had been a Waymo passenger on driver-assisted rides in Mountain View, California, in 2016 and 2018, strapped into an Argo AI that swept around the tight curving streets of Pittsburgh, and taken a ride in an Aurora through downtown Palo Alto.

He even rode a Zoox on Lombard Street in San Francisco, past multiple double-parked cars, an active construction zone and busy cross traffic — “just the firehose of craziness,” he told me.

But this was different: His first trip in a Level 4 vehicle, meaning “fully autonomous, no human in the loop, within a certain geofenced domain,” he said.

Levels of Automation

The Society of Automotive Engineers defines levels of driver assistance technology from zero to five. The scale progresses from no automation, “where a fully engaged driver is required at all times,” (Level 0) to full autonomy, “where an automated vehicle operates independently, without a human driver” under all conditions (Level 5), according to the National Highway and Safety Administration.

Prior to this, Niedermeyer had always ridden in AVs with a safety driver — Level 3 or below. This was something new, and he felt it.

“You’re not just putting your life in the hands of technology, with a human there just in case things go wrong,” he said. “You are putting your life in the hands of technology, period.”

Over the last several years, AV companies have come a long way in the capabilities of their systems to drive in congested, tightly gridded cities under extreme conditions. That’s one way to measure the success of the technology, Niedermeyer said.

“It’s like rock climbing.... The fact that Waymo is climbing without a rope clearly makes them a leader.”

But Waymo leads the pack when it comes to reliability, he added. It is the first company to take Level 4 vehicles to public roads, a feat Niedermeyer points to as a major demonstration of Waymo’s confidence in its self-driving software’s safety.

“It’s like rock climbing,” he explained. “You can climb a really hard course. Or a really easy course without a rope. The fact that Waymo is climbing without a rope clearly makes them a leader.”

Ryan Powell is head of UX research and design at Waymo, and has played a key role in the development of the ride-hailing app and the interface features of Waymo One’s two cars: the Chrysler Pacifica and Jaguar I-PACE.

Since January of 2017, he said, Waymo has completed 100,000 trips with members of the public. The program was put on pause in March, due to COVID-19 concerns, but at the time, 5 to 10 percent of the rides it offered were driverless.

This week, the company announced the re-opening of the program, along with plans to invite new customers into the fold. Waymo CEO John Krafcik said the plan is to “have general access to anyone who chooses to download the app,” Bloomberg reported.

That app, available on Apple’s App Store or the Android Play Store, will feel familiar to anyone who uses Uber or Lyft, and the service is comparable in cost. You plug in your destination. You get a price and ETA.

Driverless Cars Are Not Just for Joyriders

People from all walks of life have used the service, Powell said, including, most notably, parents with young children. One participant routinely takes her three-year-old child to daycare in a Waymo One, buckling him into the dedicated child seat and stopping for coffee at Starbucks.

But earning trust in self-driving cars among riders — not just joyriders and journalists out for a test drive, but workers commuting to jobs, parents dropping off children at school or daycare, retired couples visiting relatives, those with limited mobility access — remains one of the biggest hurdles to widespread adoption.

Citing PAVE polling data showing 48 percent of Americans report they “would never get in a taxi or ride-share vehicle that was being driven autonomously,” Niedermeyer said public acceptance levels for self-driving cars remain very low.

This is due to a number of factors, but several widely publicized AV accidents in recent years haven’t helped. A National Traffic Safety Bureau investigation of a fatal 2018 crash of a Tesla Model X in Mountain View, for example, cited the safety driver’s over-reliance on Tesla’s Autopilot (he was likely playing a game on his iPhone when the accident occurred), along with the limitations of the collision avoidance systems, as key factors in the crash.

“Putting somebody in the driver’s seat and expecting they’re going to be ready to take over, at a moment’s notice, is a very difficult thing for people to do.”

Niedermeyer said such high-profile accidents often follow a similar pattern — the result of driver inattention in vehicles with conditional autonomy. Level 2 cars, like the Tesla in the Mountain View accident, have automated functions such as lane centering and acceleration controls, but still require drivers to monitor them at all times. Level 3 cars mostly drive themselves, but the driver must be ready to take control on short notice when things go wrong. Because drivers over-rely on autonomous systems to do things they aren’t trained to do, or because autopilot encourages them to tune out and relax, drivers can be prone to making mistakes in tense situations.

Waymo, however, is banking on full conversion to Level 4 vehicles, at minimum, to push them past this critical stumbling block.

“We think the interaction model of putting somebody in the driver’s seat and expecting they’re going to be ready to take over, at a moment’s notice, is a very difficult thing for people to do,” Powell said.

Still, when a car pulls up without anyone driving it, why should you trust it? This was the question running through Niedermeyer’s mind when he stepped inside the Chrysler Pacifica: “Why do I trust this company so much? Why do I trust them enough to get into this vehicle?”

Part of the answer came from the company’s decade-long testing and validation history.

Yet the UX design was also crucial to building trust. Without a driver to say hello, reassure passengers they’re headed in the right direction or give a nod to a pedestrian hurrying across a crosswalk, fully driverless cars need to communicate their awareness to passengers to put them at ease.

For Waymo, Powell said, that begins with a rich interface display, clear affordances and voice feedback. We spoke with him and Niedermeyer about how experience design can inspire the ultimate measure of trust in technology: putting your life in its hands.

Transparent Design Engenders Trust

Translating what the car can “see” and what its intent is, to the visual interface, is a key aspect of building trust, Powell told me.

“We think of that passenger screen interface as a proxy for the communication that happens today between a human driver who’s usually up front, and somebody who is riding in the back,” he explained.

Waymo One “sees” through a sensor array that provides a 360-degree view of the surrounding environment: vehicles, traffic lights, cyclists, pedestrians, and other features. The system is highly complex, but at the most basic level, it consists of a Lidar laser detection system, cameras, electromagnetic radars, accelerometers and audio detection tools. The data from these systems is converted into images that appear on the interior display.

But the car’s POV does not look like a live feed. It is depicted as a three-dimensional map view that resembles a video game. A three-quarter bird’s eye tracks the car as it follows a green path. The street is populated by rendered images of the surroundings. Other vehicles appear as the ghosted outlines of rectangular 3D boxes.

Not only does the passenger interface show riders what the car sees — it also displays trip information and allows riders to do things like speak to a live rider support agent, request that the car pull over, or provide feedback on the car’s driving. A safety video presented to all first-time passengers reminds them to wear their seatbelts, and reviews basic rules — like not taking over the wheel.

“We know from our user research that people tend to think of other people as first-class objects.”

But the interface doesn’t tell the whole story, and this is intentional. For riders new to self-driving vehicles, the full picture of what the car sees can be overwhelming. Some of the data that might be intriguing to a software engineer — like the hovering numerical predictions of nearby objects’ speed and trajectory — is removed from the user interface.

Pedestrians and cyclists, on the other hand, are rendered in richer, more exacting detail to reflect peoples’ heightened concern for human welfare.

“We know from our user research that people tend to think of other people as first-class objects,” Powell said. “So when we use the laser points from Lidar, you can actually see their arms and legs move. You can imagine if we had used abstract symbols to represent pedestrians or cyclists, they would feel less human.”

Clear Affordances Also Enhance Trust

During a ride, situational feedback is important to ensure riders’ psychological comfort. In a ride-hailing situation with a driver, if the light is green and the car is stopped for more than a moment, you might ask why. But a self-driving vehicle needs to be more explicit in revealing its intentions.

Voice feedback allows Waymo to personalize messages and convey things that are easier to hear than to see, a company spokesperson explained by email. For example, when the car starts to move, a passenger might hear, “heading to work.” Similarly, when getting close to the destination, a voice tells the rider they’re arriving soon and reminds them to collect their things.

The automated voice also pipes up in so-called “look-up moments,” Powell said, when a rider might glance up from their mobile phone to see that the car has stopped inexplicably. Because the car’s camera and Lidar sensors are mounted on the roof and capture a panoramic view, it may be seeing something a passenger can’t, like a cyclist pulling close from the bike lane.

Moments when riders are entering and exiting the vehicle are especially important to get right, Powell told me. When you approach the car with the mobile app, a Bluetooth signal unlocks the door. Inside, a big blue button offers a clear way to start the trip.

“One of the engineers that I work with, he coins it ‘spa music,’ but we do have some backing music that plays when the door opens.”

Sometimes, though, building trust is about what not to do: “On the one hand, you might think, it’d be really cool if the door automatically opened. And it’s true. But it’s probably not going to be a good experience if it’s 2 a.m. and you’re getting out of the bar, and the car is waiting for you on the street corner and the doors open. That would be a much scarier experience,” Powell said.

Still, the car needs a touch of personality to make people feel comfortable inside it. What you don’t want is for people to sit in uncomfortable silence. Hence, the option of streaming music via Google Play.

And another small touch: “We found early on it’s a little awkward to get into a completely silent car — especially when it’s empty — so one of the engineers that I work with, he coins it ‘spa music,’ but we do have some backing music that plays when the door opens.”

People’s Alone Time Is Worth Protecting

Even though it’s important to give riders cues as to what is happening around them, there is also the danger of overkill, Powell said. A core part of Waymo’s value proposition — and what could set the company apart from driver-assisted ride-hailing services — is privacy. Powell equates privacy with the principle of user freedom: in essence, giving people their headspace.

“When you’re not being driven by a stranger, in a stranger’s car, you really have this vehicle that’s all to yourself, right? So we want to be very careful about the user experience and make sure we’re not too intrusive when you’re riding,” he said.

That means voice automation is used sparingly. The interface is kept clean, and focused on the trip route. There is no YouTube option, as Niedermeyer pointed out.

“When you’re not being driven by a stranger, in a stranger’s car, you really have this vehicle that’s all to yourself.”

Consistency is another lynchpin of the value proposition, and something the design team has mapped across all the touchpoints of the business, from the mobile app to the interior interface to the vehicle’s road interactions. The first experience people have with Waymo is not typically riding one, Powell said, but when they see a vehicle driving or stopped on the street.

And glitches have been reported.

In a September 30 tweet, Ziv Salzman, a self-described foodie, coder and sometimes blogger, shared a video with the caption, “@Waymo can you please explain how come the engine is on and there is no one inside for more than ten minutes.”

The same day Waymo replied, “thanks for bringing this to our attention! Could you please share any relevant information (time, location, etc.) so we can investigate the incident properly. We’re on a mission to make it safe for people to get around, and we’d very much appreciate your support.”

Salzman picked up the thread by providing details via Twitter.

This sort of public feedback loop is part of the product team’s learning process, and captured in a number of recent interactions on the social site.

A Slow Approach to Scale

Waymo has taken a slow, incremental approach to scale and, at times, been publicly criticized for doing so, Niedermeyer said. Whole Mars Catalog, which describes itself on Twitter as “part 24 hour EV news channel, part shitty stand up comedy routine,” recently tweeted, “Autopilot has seen the world. Waymo has seen Chandler, Arizona.”

The dig is characteristic of the sentiment of some skeptics, who claim the company is moving too slowly to effect broad change. But, as Niedermeyer said, Waymo’s long history of testing and validation is part of the reason he had few reservations taking a ride in its fully driverless car.

“It’s kind of the ultimate sign of trust: When parents are bringing their young kids with us in the car.”

And indeed, the empirical evidence in support of Waymo’s safety record is compelling.

A peer-reviewed article by Eric Teoh and David Kidd, researchers at the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, found that “Google cars had a much lower rate of police-reportable crashes per million vehicle miles traveled than human drivers in Mountain View, California, during 2009–2015.” The rate was 2.19 per million for Google versus 6.06 per million for puny humans.

In the article, published in the Journal of Safety Research, the authors also noted that “the most common type of collision involving Google cars was when they got rear-ended by another (human-driven) vehicle. Google cars shared responsibility for only one crash.” (Waymo split from Google in 2017, but the two companies still operate under the same parent company, Alphabet).

It may be that the technology gains acceptance in the way of Airbnb or Uber: People experiment with it due to its affordability or convenience and come to trust it through repeated experiences and exposure to more and more people who use it.

“We’re trying to bring to market something that is a much safer option for getting from point A to point B, and that’s accessible to a wide, diverse set of folks,” Powell said. “We’re not building a $100,000 car that only people here in Silicon Valley can access and afford to drive.”

Interestingly, parents with young children are being courted as early adopters. Each Chrysler Pacific, Powell said, is equipped with one child seat and one booster seat to accommodate their needs. For parents who would otherwise have to lug around a car seat to ensure their children could ride safely — and legally — in an Uber or Lyft, this would appear to be a clear advantage. To Powell, it is also powerful evidence of consumers’ growing trust in the software.

“It’s kind of the ultimate sign of trust: When parents are bringing their young kids with us in the car.”